In the most recent Issue of the Oddball Stocks Newsletter, our guest writer "SomethingClever" (on Twitter) wrote about the effect that the increase in the ten year bond yield has had on banks:

At the end of 2021, all US banks held about $4.3 trillion of AFS securities and $2.1 trillion of HTM securities. The cumulative mark between the fair value and amortized cost on those bonds was negative $9 billion, which equates to a -0.1% mark. As of June 30th however, that mark ballooned to negative $475 billion or -7.3%, with over half of that mark hidden in the HTM bonds.

Now, you may be reading this and thinking to yourself that a 7.3% loss does not sound so bad in the grand scheme of things. In fact, there are plenty of bond funds out there with worse track records this year-to-date. But what is needed to round this picture out is that banks typically run leverage at 10:1, meaning they hold 10% of their assets in equity, and on the left-hand side of the balance sheet securities usually represent anywhere from 20-30% of assets. This means that any loss on a securities portfolio owned by a bank has a 2-3x multiplier on its impact to its equity. Thus, despite the fact that the 10yr yield has yet to even scrape the levels it was at leading up to the global financial crisis (GFC), banks have taken marks that are triggering TCE ratios last seen during the 2008 downturn.

This is something that we have been talking about in the Newsletter for a long time. In our Issue 19 (back in March 2018), we wrote some "Thoughts on Small Banks and Interest Rates":

During last year's (2017) annual report season, we looked at 33 different tiny banks with an average market capitalization of $55 million. Most of these are not SEC filing and many provide their financial statements only to shareholders.

What we found last year was that the small bank stocks had become quite expensive. The 33 banks had a combined market capitalization of $1.8 billion compared with a book value of $1.5 billion – they traded at 1.2 times book value. Another way to look at valuation is earnings: the banks earned a combined $110 million, so they traded at 16 times earnings.

At that earnings multiple the banks were cheaper than the S&P 500 which traded at 25 times. But these banks, which are very small and mostly rural, have different risk-reward characteristics than the S&P 500. From their base of $1.5 billion of book equity, they have levered up over nine-fold to own $14 billion worth of assets. Looking at each of the 33 annual reports revealed that the majority of them have chosen to boost income by buying long duration fixed income securities. It was common for them to have invested multiples of their equity in low yielding government debt with significant duration.

Imagine a bank with twice its equity in ten year treasury bonds. These will fall in value by about 9% if the yield on the ten year treasury increases by 1%. The leverage of owning twice as much ten year bonds as it has in equity magnifies the loss twofold, so book value would fall by 18 percent. Given the six percent average earning yield on the 33 banks that have reported earnings to us so far, this small interest rate move would wipe out three years of earnings. And this does not even consider the diminution in value that the loan portfolio would experience. (Although this would not show up as a loss in the financial statements, since the loans are not revalued higher or lower based on interest rate changes the way trading securities like government bonds are.)

Of course, the rising interest rate scenario we are talking about is no longer purely a hypothetical. The yield on ten year treasuries rose from a low of 1.37% in June 2016 to its current level of 2.85%. It will be very interesting to see what kind of damage this did to the small banks' equity in 2017 annual reports. (Of course, they will still report positive net income, because changes in bond portfolio values hit the balance sheet through Other Comprehensive Income.) [...]

What we see with small bank stocks is that the situation has inverted over the course of the recovery since 2009. In the beginning they were trading at big discounts to book value and the risk-reward tradeoff of their bond investments was much better. Now that bond yields are lower they are leveraging up and buying more. And meanwhile they are trading at a premium to book value.

Our experience with these small banks is that the people running them are the dumb money. When they are so sanguine about interest rate risk that they respond to falling yields by leveraging up a couple more turns to maintain the same interest income, it seems like the final innings of the bond bull market.

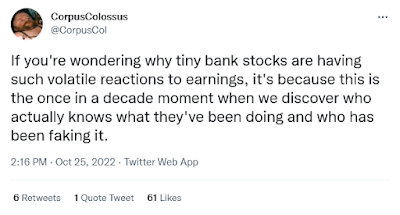

It is debatable whether the great bull market in bonds (which started in Autumn 1981) ended two years ago (summer 2020), but what we do know is that the small increase in rates off of the bottom has caused big losses for banks that were heavily invested in bonds. In his guest piece, SomethingClever wrote,

For the first time since 3Q17, and really the first time in earnest in over a decade, there are banks with negative equity capital, which admittedly is a hard thing to conceptualize. As of June 30th, there are 9 bank subsidiaries with negative equity capital. Going back quarterly, the last time there was a bank in this shape was in the third quarter of 2017: Farmers and Merchants State Bank of Argonia. Going back further on a quarterly basis, there have been 197 instances of banks ending the quarter in a negative equity position since 2000. Narrowing this down, it’s really only 151 banks in total because some banks during the crisis were in this position for multiple quarters. Of these 151 banks, 139 no longer exist, either they were acquired or absorbed by FDIC and sold off.

Excluding the 9 banks that ended June 30th of this year with negative equity, only 3 banks out of 142 made it through and still exist independently today. That is an appallingly low base rate of survival, but of course those banks had negative capital because of credit impairments, while this recent crop has negative capital because of “temporary” losses on securities that most expect to be paid in full at maturity.

In addition to the 9 banks with negative equity that were mentioned in the article (all of which were private and not OTC-listed), we also had a list of public banks that lost more than a third of their equity in the first half of 2022. Some of these have probably been pushed into negative equity with the interest rate move during the third quarter, including - almost certainly - Mauch Chunk Trust Financial Corp. (MCHT) in Jim Thorpe, PA.

This paragraph was in their second quarter of 2022 letter to shareholders:

Total shareholders’ equity capital on June 30, 2022, was $838 thousand, $46.7 million less than 2021. Lower equity capital this year is the result of a $50.5 million increase in accumulated other comprehensive loss associated with the change in the value of the securities portfolio resulting from an increase in the level of interest rates. This decrease was partially offset by an increase in retain earnings of $4 million. MCTFC’s capital remains well above the regulatory minimum requirements to be considered well capitalized.

MCHT is an interesting case study. At the beginning of the year it had $49 million of equity, $624 million of assets, $367 million of securities ($199 million due after 10 years) and a $40 million market cap (0.83x book).

As of June 30th, it had only $838k of equity and a $27 million market cap (33x book). They earned $1.4 million (excluding securities losses) in Q2 so that is under 5 times annualized earnings - assuming that their deposit cost doesn't go up.

Their deposits are almost all interest bearing. Interest expense was $394k in Q1 and rose to $503k in Q2. (Cost of funds 26 bps in Q1 vs 34bps in Q2.)

Interesting to think that with a further increase in funding cost of probably less than a percent, they would no longer be profitable.